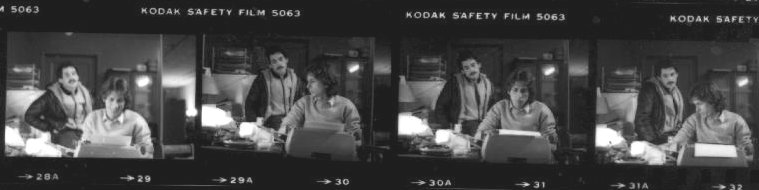

Richard Berkowitz (left) and Michael Callen writing “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic.” Duane Street, New York , late 1982 or early 1983. Photos by and cheapest 24h generic levitra © Richard Dworkin.

“The earliest safer sex advice for gay men was published in 1982. In this year, Bay Area Physicians for Human Rights, a group of lesbian and gay doctors, published a leaflet on Kaposi’s sarcoma in Gay Men; Houston’s Citizens for Human Equality produced Towards a Healthier Gay Lifestyle: Kaposi’s Sarcoma, Opportunistic Infections and the Urban Gay Lifestyle, What You Need to Know to Ensure Your Good Health; and the fledgling Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in New York published their first Newsletter . . . and distributed a quarter of a million copies of their Health Recommendation Brochure to local gay bars in November and December 1982. In 1983 these were joined by further publications from GMHC, a booklet by the cheapest 24h generic levitra Harvey Milk Democratic Club of San Francisco entitled Can We Talk?, and Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen’s How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach.

With the notable exception of the last publication, these materials did not speculate on the relative safety of specific sex acts, but instead recommended three main types of behavior modification: reducing the number of different sexual partners; eliminating the exchange of body fluids during sex; and ‘knowing your partners’ by avoiding places characterized by sexual anonymity, such as bathhouses . . .

It was How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach which pioneered the approach to safer sex which we recognize today. It was virtually the medicaments en vente libre cialis only safer sex publication which proposed a specific theory of what caused AIDS, on which its advice about specific sex acts was based. Berkowitz and Callen were patients of Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, a New York physician with a general practice consisting largely of gay men, and their booklet reflected his judgement that AIDS was caused by repeated exposure to semen containing CMV, a herpes virus which is relatively common among gay men. Sonnabend’s multifactorial theory also posited that ‘foreign’ sperm itself was immunosuppressive. The authors recognized that ‘if a new, as-yet-unidentified virus is responsible for AIDS, the measures proposed to prevent CMV transmission are likely to be effective in preventing the spread of any such virus,’ and indeed, the behavior changes suggested in How to Have Sex in An Epidemic, such as the use of condoms for anal sex, would also have prevented HIV transmission . . .

By deducing a means by which gay men could continue to ‘have sex in an epidemic’ but take rational precautions to make that sex safer, How to Have Sex in an Epidemic provided the model for safer sex campaigns for gay men ever since. As it made clear, ‘the key to this approach is modifying what you do — not how often you do it nor with how many partners.’ . . .

Berkowitz and Callen’s booklet was absolutely explicit in distinguishing between the risk of disease transmission through gay sex, and the act of sex itself: ‘Sex doesn’t make you sick — diseases do.’ In this, it was among the first responses to AIDS which acknowledged the importance of maintaining and building gay esteem, not for purely ‘gay-political’ reasons, but as a fundamental part of successful safer sex education.”

— Edward King, Safety in Numbers