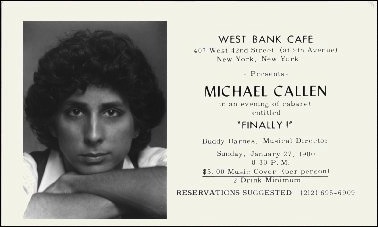

Leading AIDS activist Michael Callen singlehandedly redefined the public’s concept of a person with AIDS after his diagnosis with the disease in 1982 by giving speeches, writing articles, appearing on national television, giving interviews, organizing within the community, campaigning, and singing at a tempo that would exhaust most healthy people. His political efforts have been chronicled in Randy Shilts’ classic book, And The Band Played On. His musical output is nothing less than amazing, and includes recording two albums as one of The Flirtations (see listing). His debut solo release was recorded six years after Michael was diagnosed with AIDS, had established the PWA Coalition and testified at Congressional hearings on AIDS. Purple Heart is nothing less than the most stunning gay album recorded to date. The album has a pop/rocking set that segues into a more intimate set of six songs with Michael at the piano, and contains the classics “Living In Wartime,” “Love Don’t Need A Reason,” and Callen’s ultra-campy reading of “Where The Boys Are.” This amazingly affirming album sets the standard by which all gay albums will be judged for years to come. It is a must-have by an outstanding human being and hero to our community with one of the most wondrous voices ever recorded, and about whom Elizabeth Taylor said, “His life is a shining symbol of hope, strength and courage.” His impact will be felt on this community for years to come.

This interview was conducted with Michael shortly before his death in December 1993.

Special Online Version Of The Michael Callen Review and Interview–Complete. Copyright 1994 by Will Grega (PopFront@AOL.com)

Describe your music and what you do in your own words as an out gay person.

I sing and write about my own experiences, and my favorite art is art that comes from the specific truth of an experience. As an openly gay man, and as a man with AIDS, I couldn’t imagine any other way of writing songs which didn’t deal with being gay in a deeply homophobic society. At this late stage in my life, people tell me it’s radical and courageous, but it’s really laziness, because I can’t imagine any other way of writing. I find it absolutely astounding that the experiences of 5-10% of any given population never, ever are heard in any kind of mainstream way. We gay people are constantly expected to be able to translate the divas (“Oh, my man I love him so…”) into our own experiences, and I think straight people are perfectly capable of translating gay to straight. If I’m singing about loving another man, they should just sort of say: How is that like what I feel…gee, that’s exactly like what I feel! It’s the emotion that is universal. I’m a big fan of the details and the specifics, and there are gay cultural references that sometimes make my songs less acceptable to uneducated or unsophisticated straight people. It isn’t my intent to cut them out, I’m just not interested in concealing who I am, and since I am a gay man, often my songs reflect that experience.

Is it important to reach out to mainstream America?

I crossed that bridge a long, long time ago. I think anybody that tells you they wouldn’t like to be rich and famous is lying to you. My friend Cris Williamson, who I adore, has taken a lot of heat because she doesn’t feel she writes “Women’s Music” only for women. She writes as a woman hoping that there is some universal truth that men and women can learn from and enjoy. A lot of people used to say that was a cop-out, but I definitely have come around to her way of thinking. You have to make the best art you can make and put it out there, and it will have a life of its own. Your art will speak to straight people or it won’t. I don’t believe in pulling any punches; I don’t censor, afraid people might miss the references in my lyrics. Other artists make different choices.

Where did you come from? What was your upbringing and education?

I am an escaped convict from the bowels of the Midwest. I think of myself as poor white trailer trash. But I’ve noticed that every third homosexual comes from the Midwest, one of those “I” states. I’m from Indiana. I was raised in a very religious environment, a very small town called Rising Sun, where I was a sissy and tortured and tormented until I was able to escape to go to college and discover my people. It’s been a lifetime of healing. And for me, making art and singing about that process has been very healing. And I’ve been lucky enough and honored enough in my life that people have written me and said that some of my songs have helped heal them also.

Who would you name as your personal artistic influences?

Well, I would say without question that my three major influences are: Elton John, Barbra Streisand and Bette Midler.

What has been your artistic path or journey to get where you are today?

Well, I’m going to have to make a bunch of embarrassing admissions, but after you’ve gone on Donahue and said you’ve had 3,000 men up your butt…really, you forfeit all rights to embarrassment.

This is the truth. Nobody believes it, but you’ll just have to take my word for it. Singing for me publicly has always been torture. I loathed every second of it. Touring with The Flirtations finally beat it out of me. Performing night after night and feeling the waves of love finally cured me.

I inherited from my poor father (the subject of “Nobody’s Fool”), this absolutely impossible perfectionist system of judgment, and I was constantly judging each and every note I sang: was this the best note I could possibly have sung? Did I sing it perfectly? Did I hold it long enough? Was it perfectly in tune? Did the vibrato come in at exactly the right moment? And that’s really not what singing is about. Only this last year, something about dying has caused a continental shift in my perspective, and I finally discovered what has been underneath all of that, which is joy. And I have been making Legacy mining this deep vein of joy that’s been there all along, and it has been the greatest, happiest, most artistically fulfilling time of my life. Every single song that I sing, I love! I’ve written about forty percent of the album, and the remainder of the songs are by friends or are cover tunes that I’ve loved all my life and sung all my life. And even though my lungs are three-quarters Kaposi’s, and I haven’t been feeling all that well, it’s very strange, and I’m an atheist, but the spirit descends when I sing. I’m always exhausted and limp after this channeling. But when the tape starts and I’m singing a song that I love, you wouldn’t know that I was sick until the song ends and I collapse. I am so alive in those moments, and it’s a little sad for me to realize that if I would have just gotten over myself and taken myself a little less seriously all those years, I could have had a steady diet of this joy. But it has to do with classic gay low self-esteem: I have to prove my worth, I must be perfect, I must be the best little boy in the world. There was no harsher audience than the little voice inside me saying: you’re shit, you’re nothing, you’re not a singer, who are you fooling?

And yet you have the greatest gift of the most amazing talent that is the envy and awe of all your peers. I’m glad you’ve found that joy.

I am too! When I start to get sad thinking about how much time I wasted, my boyfriend points out to me that some people die without ever having had a taste of it. I have at least had nine months of it.

There are those who say that I had a white bread or a “Wonderbread” voice and that I could have been a Barry Manilow if I’d really aggressively pursued it, and sung romantic ballads with the “she” pronoun. I would have loved to have had his fame, his money, his gold records, but I got right up to the moment where I had to sing “she” and I just couldn’t envision it. I don’t have any experience of having romantic love for “she’s.” So, my immediate response when I started out was to do something a lot of gay people in my generation did: I went through what I call my “second person” phase. I scoured the music library for songs that were gender non-specific and constructed this whole elaborate defense: Oh, it’s more universal, let the reader fill in…

Gradually, I realized that was a cop-out and I was spending a lot of energy avoiding singing my truth, “he.” It didn’t take me long to take that leap. And whether or not I was foreclosing any possibility of commercial success, I guess we’ll never know, but I haven’t regretted it at all. So far, we don’t have any examples of someone being openly gay first and becoming a successful commercial artist. Somebody’s going to do it, though.

What was the artistic path that led to your recording career?

I was a child soprano prodigy. I was a boy soprano. I realized I had a voice at an early age, a soprano voice. Then that got beaten out of me because beyond a certain age, boys are not supposed to sing soprano.

My first musical influence was Julie Andrews, “[The Lass] With A Delicate Air.” You can imagine the poor scenes with my father, as a I sang that song with a British accent. It was just not done.

Much later, in New York, I sang at Snafu and the Duplex and the whole circuit, kind of half-heartedly. Singing was agony for me, and I would throw up before a performance or lose my voice because I was tense, and I loathed every second of it. And the most frustrating thing during that time was that everybody used to assume that I was having the time of my life and that singing was the most natural, easiest thing in the world for me. They would compliment me on my natural voice, while I felt like I was pushing a piano through a transom. If they only knew…

And then the AIDS war came. My favorite myth these days is Cincinnatus, who only wanted to be a farmer but was called away from his plow to lead the Roman army to keep Rome from being destroyed. If I hadn’t been so involved in the AIDS political struggle, I would have made a lot more art. I was constantly making agonizing choices between singing/performing and giving a speech or giving testimony or chairing a board meeting.

Purple Heart came about due to my boyfriend, Richard Dworkin. I give him complete credit. I got sick and it looked really grim and he basically said: If we make it through this, I think it would be an absolute scandal if you didn’t leave the world some record of your music. So, I did recover and he agreed to spend our money and undertook to produce Purple Heart, which I thought would be a one-shot deal. I thought no one would buy it because I wasn’t prepared to tour. I wasn’t well enough to tour, and that’s really the only way you sell an independent album. And it really did drop like a stone. Very few people heard about it.

Over time, however, that changed. The people who have heard Purple Heart hold it up as the hallmark against which all gay albums should be judged. I’m very proud of it, although Legacy is an order of magnitude beyond Purple Heart. It’s just the best thing I’ve ever done. I think the difference is joy, but I’ve also had the good fortune to work with some of the best artists in the world who have been so generous to drop what they were doing to come and make this possible.

Do you think it is important for gay music to be taken to mainstream American via the big record companies?

Yes. That’s the equivalent of the “color line.” We’ll know the revolution is near when that happens. Times are changing and somebody is going to take that leap of faith starting a career as an out gay artist, and it’s going to work commercially. But I think it’s hard to convince emerging artists that that strategy is likely to pay off. Unfortunately as of this date, you can’t name a major label who has signed an openly gay artist (at least in America). The British scene is different.

You got involved with The Flirtations in 1988. How did you go from full-blown musical arrangements and a solo career to becoming a member of an a cappella group?

Well, there’s an interesting story that I told at my final concert in Washington after the 1993 March on Washington. I was a closeted soprano. I had been literally made fun of and smacked for singing like a girl, and I just happened to have these incredible pipes, only I was embarrassed about it. No one really knew. I was a tenor, so I sang high anyway, but nobody had ever heard my soprano. I met Richard in the [fall of 1982] and we moved in together and one time I was in the kitchen singing along to the radio in my best soprano, and he came running in and said, “What was that?” and I got all embarrassed and admitted it was me.

Richard slowly convinced me to expose my talent to the world. We were in a lesbian and gay rock band at the time called Lowlife, so he insisted that I sing more and more lead parts. I was horrified, waiting for people to shoot me or start laughing. It was really Richard and his love and support that enabled me to be proud of that part of my voice.

I was also so busy and so stressed out with AIDS activism that I missed The Flirtations’ notice in the Village Voice. Richard caught it and made an audition appointment without ever telling me–in Brooklyn. “What? I don’t go to Brooklyn!” And he told me it was an audition for an a cappella group and that it was perfect for me and I moaned and pissed and resisted. But I went and the rest is history…gay history…herstory. The Village Voice certainly does bring people together: it’s how I met my lover, it’s how I met Pam Brandt…and The Flirtations ad changed my life.

What is gay and lesbian music in your definition?

I think the notion of a gay community is a necessary fiction. I don’t think there is one, but I would say that it’s really useful and wonderful to pretend that there is, and to act as if there is. Gay and lesbian music is simply music made by gay and lesbian people, or music specifically about the experience of being lesbian or gay.

What is your vision of gay music? Where are we going and how far? How much of an impact can we have on the 90’s? Will gay music cross over to the mainstream and is that important?

I think there’s a step missing, an important step. Our heroic lesbian sisters have created something called Women’s Music, which of course really was Lesbian Women’s Music. They built from scratch an audience, a distribution network, and recording labels owned and controlled by women. They produced a cultural phenomenon where women supported women artists. There is absolutely no gay male equivalent of that at all, and I would say that before we talk about crossing over to the mainstream, we have to go through that community-building stage. The average gay man doesn’t begin to know what gay music is or who the “stars” of gay music even are. Hopefully, the GAY MUSIC GUIDE will help change all that.

The women are ready for mainstream success, because they have a demonstrated track record. Holly Near has sold something like two million albums in her lifetime. Any record company is going to sit up and take notice of figures like that. Cris Williamson has sold nearly a million albums. That’s the way I think you break into the industry: you prove to them that it’s in their financial interest and that there is a market, a loyal following that will buy these albums. Gay men need to do their homework. If the gay community, and gay men in particular, support gay music, the results are going to be amazing for music and for the movement.

To receive information about how to order the full-text paperback of Gay Music Guide (with photos, interviews, and artist contact information) and the 24-song cassette sampler, please e-mail your address toPopFront@aol.com. Thanks!